Everything Happens in Cable Street

ADAPTED FROM THE INTRODUCTION TO EVERYTHING HAPPENS IN CABLE STREET

I’ve lived along Cable Street and its various tributaries ever since moving into East London in the late 1970s. My first residence there was a squatted flat, half way up a tower block on the western edge of Swedenborg Gardens, named after Emanuel Swedenborg. The Stockholm Christian mystic, who claimed to be on speaking terms with both angels and demons, lived in the area, on and off, from the early 1700s onwards. The Swedish community raised a church here, in which Emmanuel was buried in 1772. The building is long demolished and with only a small stone protrusion – easily mistaken for a vandalised drinking fountain – to mark it.

I’ve lived along Cable Street and its various tributaries ever since moving into East London in the late 1970s. My first residence there was a squatted flat, half way up a tower block on the western edge of Swedenborg Gardens, named after Emanuel Swedenborg. The Stockholm Christian mystic, who claimed to be on speaking terms with both angels and demons, lived in the area, on and off, from the early 1700s onwards. The Swedish community raised a church here, in which Emmanuel was buried in 1772. The building is long demolished and with only a small stone protrusion – easily mistaken for a vandalised drinking fountain – to mark it.

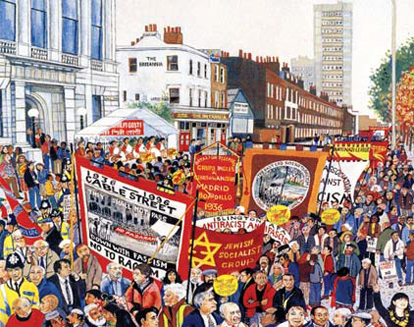

Later, I moved to another tower, further east, beyond the crossroads where the suicide John Williams, supposed perpetrator of the Ratcliffe Highway Murders of 1811, was tossed into a hole. His bones were left to rot for a century until disturbed by workmen, the skull gifted to the landlord of the corner pub, now closed and shuttered like all the others along the entire stretch. The current location of Williams’ head is unknown. My new abode was a rented GLC ‘hard to let’ flat which overlooked Watney Market, just off Cable Street. The tall metal skeleton of the structure was clad in a hard, white plastic material. And, with ill-fitting window frames rounded at the edges, unkind visitors were keen to remark on its resemblance to a pile of illegally dumped washing machines, abandoned at some forgotten roadside in a clapped-out and toxic condition. In the old, dying market below, ‘Joe the Grocer’ was still having anti-Semitic slogans daubed on his shop-front as recently as the late 1970s, many years after Sir Oswald Mosley’s fascist Blackshirts were frogmarched out of the area in the legendary Battle of Cable Street of 1936.

Another housing step has found me, now with a family, in my current location at the far eastern end of Cable Street, tapping the computer keys in a ground floor maisonette. The estate, where satellite dishes seem to outnumber the residents and teenage boys nightly sow the flowerbeds with emptied cans of Red Bull and miniature vodka bottles, is on Stepney Causeway, running between Cable Street and Commercial Road. It was on this exact site in the winter of 1870 that the Dublin born, evangelical Christian, Dr Thomas John Barnardo, opened his Home for Destitute Boys.

I’ve realised, since beginning to create this book that I’ve probably lived along Cable Street and its offshoots for longer than most of the other people contained in its pages. I use that thought to justify myself in writing – from a personal perspective – about the street and the people who have lived here. But who are they? And for that matter, what is Cable Street?

This book deals in the main not with the distant past but with a more recent remembered time. When I started work on it, I had to think hard about how I might try to present all those different memories that people told me about. It was as if there were a hundred Cable Streets, so different were the stories. And, unbidden, an image came to mind of an old-fashioned slide projector on a dusty wooden table. And next to it, a clutch of slides from the early twentieth century up to the present day. I imagined myself as the projectionist, feeding the slides into the slot, one after another. But in my haste, I fail to take any of them out: the result being an increasingly crowded montage on the screen, of shifting architecture and of different generations of Cable Street inhabitants. Pictures of skull-capped tailors with tape measures dangling round their necks, post-war US servicemen with a blonde hanging off each brawny arm, shelves of kosher food shops restacked with Halal product, outdoor toilets, rundown picture houses, dodgy Maltese cafes, tower blocks – all along the same track that is called Cable Street, each successive wave of new arrivals adding to the by now jumbled scene.